Wednesday, 30 March 2016

You don't need a learning curve to have fun

“A scout is a man who likes a change,” wrote Jack Vance at the start of his Planet of Adventure novels.

What’s true for interplanetary scouts in the Gaean Reach applies also to dyed-in-the-wool gamers. Whatever their preferred genre, they like change. They enjoy encountering new situations that test their understanding of the game. Granted, predictability provides a comforting safety net while performing those mental and pollical gymnastics. Sometimes it’s nice to know exactly what you have to do next. But consider those moments when you feel the real exhilaration of gameplay. It’s when you’re facing fresh, unexpected challenges. That’s when you get to extend your limits.

Hardcore gamers are not the mass of humanity, not by any means. We all like to feel a sense of improvement, but for most people heuristic problems are simply stressful. They don’t want to keep testing their understanding. They’re content to test their knowledge.

Think of it this way. A general has to deal with continually changing situations across multiple problem domains, drawing on his or her understanding of psychology, logistics, weapon systems, weather and so on. There’s never a dull moment when you’re Napoleon, especially when you have Ney on the battlefield.

At the other end of the scale, the ordinary soldier has a set of routine tasks and (we’re generalizing of course) all he has to do is perform them with proficiency and alacrity when he’s told to.

More people are suited to be soldiers than to be generals. There are more players than gamers, more consumers than creators, more colonists than scouts.

For the majority of us, familiarity with a place (or a group of characters) is more rewarding than familiarity with a set of rules. No doubt this was true even in prehistoric times. Asked, “How do I get something to eat?” the casual player type would respond by pointing the way to the nearest berry bush. Only the dedicated gamer would explain how to hunt.

Learning curves are only important if you think the player wants to achieve an A-level in your game. There’s no learning curve in Disneyland. Once you’ve worked out how to use the ticket book and how to fold the map, it’s all about turning discovery into familiarity. Goofy’s in the parade and the fireworks are at six o’clock. It’s interactive and it’s fun. That’s all you need to know.

Friday, 18 March 2016

Rules for status

My role-playing group has been using GURPS as our default system for many years now. Third edition was a little kludgy but the overhaul they did with GURPS 4e fixed most of that. Even if you don't use the rules, I recommend the sourcebooks.

One aspect of GURPS that we've rarely had cause to explore are the rules for status. Our Legend characters are reviled mercenaries, our Spartans characters are a law unto themselves, our sci-fi characters zoom through a Mass Effect inspired universe of libertarian laissez-faire chaos, our Ghosts of London characters are misfits who have more intercourse with spirits than with regular society. There hasn't been much call for a skill like Savoir-Faire.

Until now, that is. Tim Savin's 1890s Investigators campaign has us playing a mix of social classes, talking to people rather than fighting them, and so we've been drilling down into how GURPS handles all that.

Not terribly well, is the answer - not even in the GURPS supplement designed expressly for the purpose: Social Engineering. Probably one reason is that there is after all no such thing as a generic status system; every society is different. French writers throughout the 17th and 18th centuries were continually puzzled and horrified at the way social classes mixed in England in a way unthinkable on the continent at that time. Henri Misson de Valbourg made this observation while visiting London in the late 17th century:

If two little boys quarrel in the street, the passengers stop, make a ring around them in a moment, and set them against one another, that they may come to fisticuffs. During the fight the ring of bystanders encourages the combatants with great delight of heart, and never parts them while they fight according to the rules. And these bystanders, are not only other boys, porters and rabble, but all sorts of men of fashion.... The fathers and mothers of the boys let them fight on as well as the rest, and hearten him that gives the ground or has the worst.A bigger problem might be that GURPS is written by Americans. Hold your horses there, I don't mean any insult - simply that it makes perfect sense for an American game designer to just add wealth and social class together to get an overall status number, but in fact an impoverished aristocrat, a rich commoner and an average member of the gentry (all in GURPS terms Status 3) would not be treated as exactly equivalent even in 1970s Britain, much less in 1890.

These combats are less frequent among grown men than children, but they are not rare. If a coachman has a dispute about his fare with the gentleman that has hired him, and the gentleman offers to fight him to decide the quarrel, the coachman consents with all his heart:the gentleman pulls off his sword, lays it in some shop with his cane, gloves and cravat, and boxes in the manner I have described. If the coachman is soundly drubbed, that goes for payment; but if he is the beater, the beatee must pay the sum for which they quarrelled. I once saw the late Duke of Grafton at fisticuffs in the open street with such a fellow, whom he lambed most horribly. In France, we punish such rascals with our cane, and sometimes with the flat of the sword; but in England this is never practised. They use neither sword nor stick against a man that is unarmed, and if an unfortunate stranger (for an Englishman would never take it into his head) should draw his sword upon one who had none, he'd have a hundred people upon him in a moment.

And then there's what higher statuses actually mean. When I visited Bali in the 1980s you'd meet Brahmins - usually not so well off (because they wouldn't stoop to wheedling cash out of tourists) but on the top rung when it came to status. But high status in late 20th century Bali means a very different thing from high status in mid 18th century France. The same numbers of status levels may separate high from low, but what does that translate to? It all depends on the society - indeed, on the sub-stratum of society you're considering. In War and Peace, Field Marshal Kutuzov has lower status than some of the junior staff officers at court. Even a lieutenant can keep him waiting at a whim. Yet on the field, among his own men, presumably Kutuzov's status is very much the higher.

Status and social class have always been important factors in our Tekumel campaigns. There it matters not only which clan you belong to, but also the status of your lineage within the clan. A comparison might be: is it more prestigious to be a commoner at St Peter's College or head porter at Christ Church? A complex issue. In Tsolyanu, if you join a legion or the civil service, your rank doesn't simply add to social status as it does in GURPS. Rather, your social class determines the rank you are likely to rise to. Any damned fool of the aristocracy can become a junior officer in a medium regiment; after that, further advancement depends on ability and bribes (wealth). But that's Tsolyanu. In other societies, wealth might not count for so much, or might count for more.

Friday, 4 March 2016

Game write-ups

Game write-ups make for notoriously bad fiction. It’s not that surprising. “What happened in last night’s game?” someone asks, and we’ll trot out a great wodge of incident. But a story is much more than incident, as the Master reminds us. Incident – that is to say, the plot – is just the foundation. On that a storyteller builds the real narrative, which is a personal journey of change. Fighting a shoggoth has to mean something. You know this; you’ve seen “The Body”.

Game write-ups make for notoriously bad fiction. It’s not that surprising. “What happened in last night’s game?” someone asks, and we’ll trot out a great wodge of incident. But a story is much more than incident, as the Master reminds us. Incident – that is to say, the plot – is just the foundation. On that a storyteller builds the real narrative, which is a personal journey of change. Fighting a shoggoth has to mean something. You know this; you’ve seen “The Body”.

The best games would anyway make the worst stories. Fiction is designed to have endings that are “surprising yet inevitable”. We know Luke has to hit the thermal exhaust shaft, we just don’t know how he’s going to hit it. But we don’t want games to be inevitable, we want them to be like a second life. And our lives, engrossing as they are to us, don’t have the neat symmetries and moral and thematic patterns to be found in a work of fiction. The only way to achieve that effect in a game is if the referee (“games master” to me evokes a low-wattage sadist in a rugger shirt) twists events to come out the way he or she wants them to – which is the antithesis of good roleplaying. Not only must it be possible for defeats to occur, but they might be pointless. Shit must be able to happen - as, in our play-through of this adventure, it most definitely did.

All that aside, background incident is a useful resource to a writer. A lot of creative writing graduates could do with more of it. So in theory it should be possible to grow a good work of fiction out of a roleplaying game. Raymond E Feist infamously based a lot of his early novels on Tekumel campaigns. Still, we were talking about good fiction… I have been pestering Paul Gilham to turn his blisteringly brilliant Ghosts of London campaign into a novel. Paul demurs because I’m sure he realizes that all that meticulous plotting, vital though it is, is only the start. He’d need to break it all apart, insert a character with a need to change, and let us see the succession of plot events as the conduit for that change.

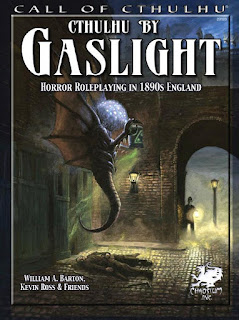

I did none of that with this write-up for our current 1890 campaign run by Tim Savin. It’s just the bare events of the game, albeit in the voice of my character. But it might be of interest because it’s based on a published scenario (“The Night of the Jackals” from Cthulhu By Gaslight 3rd edition) and because it gives a glimpse of our own games, which some of this blog’s readers have enquired about. Tally ho.

Labels:

1890,

Cthulhu,

fiction,

Ghosts of London,

GURPS,

Henry James,

Joss Whedon,

Oscar Wilde,

Paul Gilham,

Raymond E Fe'ist,

role-playing games,

storytelling,

Tekumel,

Tim Savin,

Victorian,

write-up,

writeup

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)