The Dragon Warriors RPG is set in a place called Legend*. But what is the world of Legend like? That was a question a new player in our campaign posed recently. One of the veteran gamers said, ‘All you need is to read the Vance short story “Liane the Wayfarer” and you have the whole thing – the humour, the vibe, the chances of success.’ That surprised me, flattering though the comparison is, as the Legend in my head (which is no more valid than any other, of course) is utterly unlike the Dying Earth. Blood Sword features a higher fantasy variant of DW's Legend, but it still doesn't come close to the flamboyantly fantastical world of Mazirian, Rhialto, Cugel and co. Much as I love Vance’s work, even the relatively restrained Lyonesse** is much more magic-drenched than most of Legend.

Pressed to come up with some sources to convey the flavour of Legend to a newcomer, I started out with movies like The Seventh Seal (Bergman), Dragon’s Return (Grečner), The Hour of the Pig (Megahey), and The Black Death (Smith). None of those looks exactly like Legend but there are elements I recognize. Richard Carpenter's Robin of Sherwood actively inspired me when writing DW, to the extent that Clannad’s ‘The Hooded Man’ was part of our Legend gaming soundtrack in the ‘80s. The show depicted the level of magic that I think people in Legend would believe in, as do Dragonslayer (Robbins) and The Northman (Eggers).

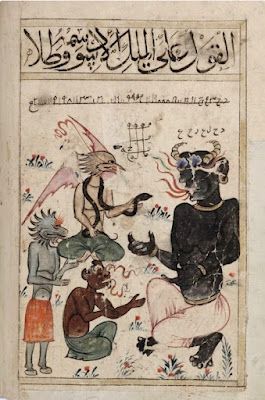

Not quite like Legend but still worth plundering for ideas are Hero (Platts-Mills), which is especially good for the malice and craftiness of the fays, Jabberwocky (Gilliam) for all the mud and shit, Flesh & Blood (Verhoeven) which is set three centuries too late for Legend but reminds us that it’s a time when for many life is nasty, brutish and short, and a claymation film called H (Simpson) to which Ian Livingstone introduced me and which is great for the hallucinatory madness of medieval religion and superstition; it's where the image at the top of the post comes from.

Further out still are a few movies I feel share some common ancestors with Legend. Excalibur (Boorman) and The Singing Ringing Tree (Stefani) are both absolutely shot through with epic fantasy but with a subtle core of folklore. Every time a DW mystic works their magic, you feel the Dragon’s tail give a twitch. Viy (Yershov & Kropachyov) is brimming with febrile fantasy and gloriously rough and dreamlike '60s special effects. I like King Lear (Brook) and Macbeth (Polanski) for flavour. And, surprising though it is to say it, Pillars of the Earth (Mimica-Gezzan) has something to offer to the Legend referee even if it’s only Ian McShane’s performance.

That’s movies. In other media I recommend Kingdom Come: Deliverance (Warhorse Studios) and Crécy (Ellis), both a century or two too late to really reflect Legend. And when it comes to novels, the Legend take on elves was definitely influenced by Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword and Michael Moorcock’s Silver Hand trilogy. They swiped it all from Scandinavian and Celtic myth, of course.

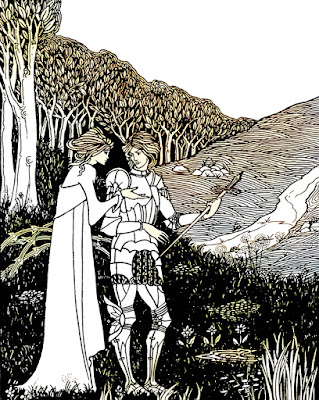

Talking of Celtic myth brings me at long last to the main point of this month’s post, which is to tell you about David H Keller’s Tales From Cornwall. Some of these were serialized in Weird Tales in 1929-1930 and again in the 1970s by Robert ‘Doc’ Lowndes in his Magazine of Horror, which is where I came across them. They’re in the genre of new folktales, establishing a fantasy history for Keller’s own Cornish ancestors. Here’s a taste:

The stories are slight, at times not quite making sense (they’re very authentically like a lot of Celtic myths in that way), but what I like are the atmosphere and the tone, especially in the Cecil stories that start with ‘The Battle of the Toads’. There’s a subtlety missing from most pulp fantasy too. At a time when most heroines have to be Bêlit the she-pirate, carousing and mixing it up just like the men, Keller’s strong women are clever enough to achieve their goals despite the constraints put on them by their society.

We don’t have the last five stories. If anyone happens to have access to Syracuse University library, they could pop in and read them, but it seems unlikely that they’ll get into wider circulation until at least 2036 (when Dr Keller’s work enters public domain). I just hope Syracuse University keeps the manuscript safe till then.

Still, we have the first ten stories and in them there’s a little bit of the DNA of Legend. Try them -- you’ll find that for century-old yarns they are surprisingly fresh in places, and despite lashings of fantasy it feels like they’re still on the ‘realist’ edge of that long misty border into Elfland.***

*But not by its inhabitants. That is, Legend is a non-diegetic term for the setting. If you ask a DW character they'll call it "the world" or "the middle world".

**There's a Lyonesse RPG of which I happen to be one of the writers.

***This entire post is an abbreviated version of one from my Patreon page. Come and join the fun, even if its only as a free member, and get the complete article and a lot more besides.

-detail.jpg)